High above the ancient road that once connected Babylon and Ecbatana, where merchants, envoys, and soldiers passed beneath the shadow of limestone cliffs, rises a monumental voice carved in stone. The cliff at Bagastâna, meaning “place of the gods,” was no ordinary rock — it was a sacred landmark commanding the crossroads of empires. Here, around 520 BCE, Darius I the Great inscribed his story for the world to read: a tale of divine selection, rebellion, and restoration.

The Behistun Inscription, as we know it today, is both a work of art and a political manifesto — the ancient world’s most audacious declaration of legitimacy. It tells how Ahura Mazda chose Darius to overthrow a usurper and to restore asha — truth and order — to the world. Yet buried within this triumphal rhetoric lies one of antiquity’s most enduring riddles: the mystery of the false Bardiya, the shadowy figure whose death gave Darius his throne.

1. The Rock That Spoke to Empires

The site of Behistun (modern Bisotun, Iran) lies 30 kilometres east of Kermanshah on the old imperial road between Mesopotamia and the Iranian plateau. In antiquity, it was already known as sacred ground. Its name, Bagastâna, literally meant “the place of the gods,” perhaps referring to the sheer height of its cliffs or to older Elamite sanctuaries that once dotted the region [1].

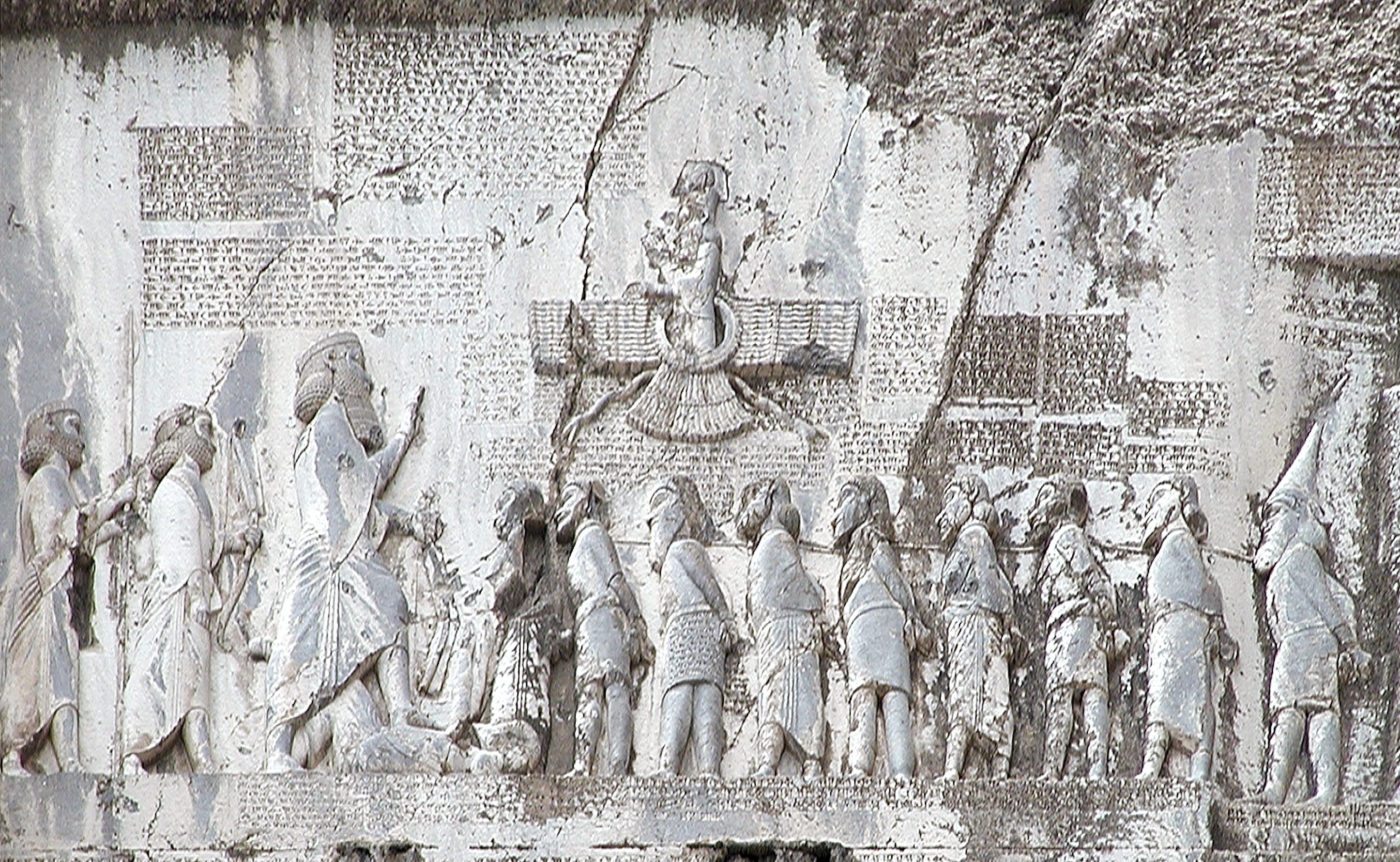

Here Darius ordered his artisans to carve a relief about 15 metres high and 25 metres wide, positioned roughly 100 metres above ground level, where travellers could see it but none could deface it. The monument depicts Ahura Mazda hovering above Darius, who stands over a prostrate enemy identified as the usurper Gaumata, while nine other defeated rebels approach in chains.

To the casual eye it is a celebration of victory; to the careful reader, a manifesto in stone. Beneath the relief, Darius dictated a text in three languages — Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian — totalling more than 1,100 lines. The words proclaim not only how he seized power, but why his rule was divinely justified.

2. Engineering Faith in Stone

The creation of Behistun was a feat of logistics and theology. Workers carved scaffolding into the rock face, hauling tools, pigments, and water up steep ledges. The surface was first polished, then incised with outlines before stonemasons chiselled the final relief.

The trilingual text served two purposes: to communicate across the empire and to sanctify Darius’s truth. The Old Persian version was written for his own people — a new imperial language derived from cuneiform but simplified for clarity. The Elamite and Babylonian versions ensured that the message reached the educated elites of the empire’s western provinces [2].

In essence, Behistun was an act of translation as propaganda. By inscribing the same story three times, Darius embedded his legitimacy into the linguistic fabric of his realm.

3. The Political Crisis of 522 BCE

The inscription opens with turmoil. After Cambyses II, son of Cyrus the Great, conquered Egypt, he mysteriously died on his way back east in 522 BCE. In his absence, a man named Gaumata, described by Darius as a Magian priest, seized power claiming to be Bardiya (Smerdis), Cambyses’s brother.

According to Darius, this was deception. The true Bardiya had been secretly killed by Cambyses before the Egyptian campaign, and Gaumata’s imposture plunged the empire into chaos [3]. Darius, a distant relative of Cyrus, claims that Ahura Mazda chose him to restore order. With six Persian nobles, he stormed Gaumata’s fortress at Sikayauvatiš in Media and slew the false king.

The story is heroic, but it also raises an uncomfortable question: what if Darius’s version was a political fabrication?

Ancient Greek historians like Herodotus and Ctesias repeat Darius’s account, describing a conspiracy of seven nobles and even a contest in which Darius gained kingship by a clever ruse — his horse neighed first at sunrise [4]. Yet these narratives all derive, directly or indirectly, from Darius’s own propaganda. There are no independent records of the real Bardiya’s death. See more on Bardiya and the Throne of Deception: Investigating a Persian Mystery.

4. Decoding the Behistun Text

The Behistun inscription is not merely an historical record — it is a moral drama written in imperial language. In the Old Persian version, Darius presents himself as the embodiment of asha (truth), while his enemies are followers of drauga (the Lie).

“Says Darius the King: These are the lands that became rebellious. Ahura Mazda brought them again to my rule; by the grace of Ahura Mazda I restored what had been taken away by the Lie.” [5]

This language fuses politics and theology. Rebellion is not simply treason — it is falsehood; obedience is truth. The dichotomy mirrors early Zoroastrian cosmology, turning a civil war into a cosmic struggle.

Interestingly, each linguistic version subtly differs. The Old Persian emphasises divine grace, the Elamite focuses on royal authority, and the Babylonian on the punishment of rebels [6]. The inscription thus speaks differently to each audience — priestly, bureaucratic, and provincial — yet all align under one principle: Darius is chosen by the god of truth.

5. The Mystery of the False Bardiya

Modern historians remain divided over whether Gaumata was truly an impostor or whether Darius invented the lie of the liar.

Some scholars, such as Pierre Briant, argue that the coup was legitimate: Gaumata’s sudden appearance after Cambyses’s death and the empire’s rapid submission suggest deception [7]. Others, like Amélie Kuhrt and Wouter Henkelman, propose that Darius, an ambitious noble unrelated to Cyrus’s direct line, needed a theological pretext to justify seizing power. By labelling his predecessor an impostor, he made himself not a usurper, but a saviour of divine order [8].

In this reading, the Behistun text becomes one of history’s most sophisticated acts of narrative control. The “false Bardiya” may have been genuine — a brother returning to claim his throne — erased by a victor who mastered both sword and stylus.

The riddle deepens when one considers Darius’s obsession with erasing Gaumata’s name from every record, while his own is proclaimed from cliffs visible for miles. The inscription thus preserves a tension between history and myth: a ruler asserting truth through an act of suppression.

6. Propaganda, Legitimacy, and the Voice of the Gods

The Behistun Inscription must also be read as a manifesto of kingship. Darius did not merely recount events; he set out a new political theology.

Earlier Mesopotamian kings — from Hammurabi to Ashurbanipal — also carved laws and victories in stone, but Darius’s innovation was the fusion of divine election and moral truth. Where Babylonian kings claimed patronage from multiple gods, Darius invoked a single deity, Ahura Mazda, as both creator and witness.

By doing so, he created a bridge between Elamite royal tradition and Zoroastrian ethics. The king became the earthly reflection of cosmic order — a role that future Achaemenid rulers, from Xerxes to Artaxerxes, would emulate [9].

The propaganda was remarkably effective. Within a decade, Darius had quelled nineteen revolts, extended his empire from the Indus to the Aegean, and commissioned inscriptions in the same triumphant tone. Each echoed Behistun’s refrain: “What I have done, I have done by the will of Ahura Mazda.”

7. Rediscovery and the Modern Decipherment

For nearly two millennia, the voice of Darius lay silent, the script unreadable. Travellers saw the figures but could not understand them. In 1598, the English explorer Robert Sherley mentioned the carvings; later, Carsten Niebuhr made sketches in 1764. But it was Major Henry Rawlinson, a British officer in the 1830s, who risked his life scaling the cliff to copy the text.

Rawlinson’s painstaking transcription became the Rosetta Stone of cuneiform. By comparing the three versions, he deciphered Old Persian and, through it, the Akkadian and Elamite scripts. In 1857, the Royal Asiatic Society formally confirmed the decipherment — a turning point that unlocked 3,000 years of Mesopotamian history [10].

Thus, Behistun not only justified Darius’s reign; it resurrected the voices of entire lost civilisations. Ironically, a monument built to enforce a single truth became the key to recovering many.

8. The Enduring Enigma and the Princess of Pasargadae

The Behistun narrative reverberates beyond history — it touches the nature of truth itself. Was Darius the chosen guardian of asha, or the most successful propagandist of antiquity?

In my forthcoming historical fiction, The Princess of Pasargadae, the question of the false Bardiya becomes more than a political mystery; it becomes a moral riddle. What happens when truth itself becomes a weapon of power? When silence is enforced not by death, but by inscription?

Darius carved his story where the earth meets the sky, confident that stone could silence all dissent. Yet stone, too, can fracture. The Behistun cliff reminds us that every empire — however mighty — stands upon competing versions of truth.

9. Legacy: Stone, Memory, and the Lie

Today, the Behistun Inscription stands weathered but intact, recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Its trilingual text continues to draw historians, linguists, and travellers alike. The rebels Darius called liars are nameless, but the questions they raise endure:

- Who decides what is true?

- How does power rewrite memory?

- And when the gods are silent, whose voice becomes divine?

In answering these, the cliff of Bagastâna still speaks — not only of victory, but of humanity’s endless struggle to discern truth from the Lie.

Footnotes

- Rawlinson, H. C. “The Persian Cuneiform Inscription at Behistun,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1846–1857).

- Briant, P. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Eisenbrauns, 2002, pp. 110–113.

- Kent, R. G. Old Persian: Grammar, Texts, Lexicon, American Oriental Society, 1953.

- Kuhrt, A. The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period, Routledge, 2007, pp. 145–150.

- Herodotus, Histories, Book III, trans. Godley, Loeb Classical Library, 1920.

- Translation after Kent, op. cit., DB I: 60–62.

- Henkelman, W. F. M. “Darius and the Lie: Narrative and Power in the Behistun Inscription,” Iranica Antiqua 45 (2010).

- Briant, P., op. cit., pp. 120–126.

- Kuhrt, A. and Henkelman, W., ibid.

- Lincoln, B. “Religion, Empire, and Torture: The Case of Darius and the Magian,” History of Religions 46 (2007).

Leave a comment