“A hall open to the sky, where kings received the world.”

Introduction — What “Apadana” Means, and Why Susa Matters

The word Apadana (Old Persian 𐎠𐎱𐎭𐎠𐎴) appears in the royal inscriptions of Darius I and is generally understood as an audience hall with open porticoes—literally an “un-walled” or “open-sided” space. Architecturally it denotes a vast, columned hall whose flanking sides are open to light and air, where the king could meet embassies, dispense justice, and stage imperial ritual beneath a visible firmament.

While the best-preserved Apadana stands at Persepolis, the Apadana of Susa is older and reveals Darius’s intent to root imperial kingship in Elam’s ancient soil while projecting a universal, multi-ethnic order. Think of the two great halls as twin thrones: Susa (the winter and administrative seat) and Persepolis (the ceremonial acropolis). Together they express a philosophy of rule—open, luminous, orderly.

Foundations upon Memory — Building over Elam

Construction of the Susa Apadana began c. 521–515 BCE, on top of earlier Elamite layers. This was not mere convenience. Darius repeatedly linked his authority to Ahura Mazda’s favour and to the antiquity of Susa, a city already venerable in the Elamite age. Raising a new palace over the “land of the gods” (Elam’s own epithet) proclaimed continuity: Persia did not erase; it renewed.

Materials were drawn from across the empire: limestone and hard black stone for columns and capitals; kiln-fired, glazed bricks for facings and friezes; timber and pigments sourced through imperial supply lines. The logistics themselves—quarries, kilns, teams of craftsmen—were a demonstration of central capacity.

Architecture of Majesty — Plan, Scale, and Light

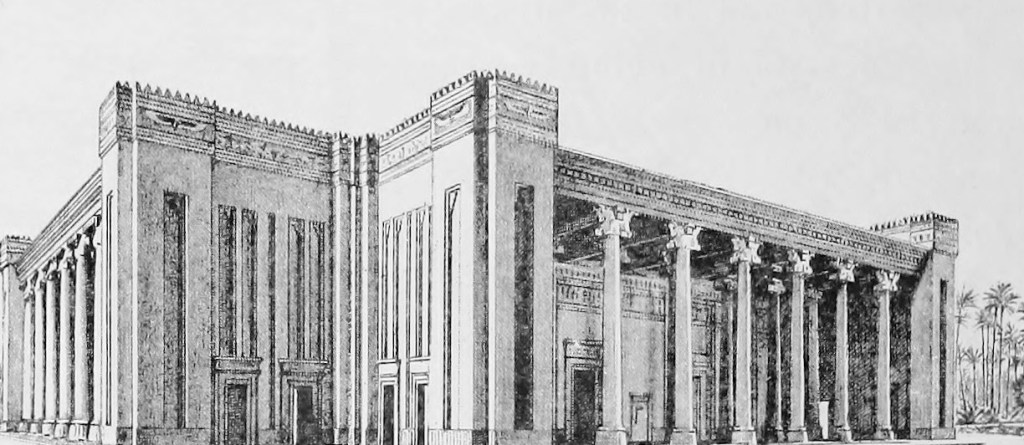

At its core, the Apadana of Susa was a square hall of c. 58 × 58 m supported by 36 columns roughly 20 m high. On the north, east, and west sides, deep porticoes extended the processional space; to the south, service and royal rooms connected to broader palace quarters. Around this nucleus, courtyards admitted light and air, stabilised temperature, and choreographed movement.

- Columns & capitals: tall, fluted shafts supported paired animal capitals—most famously bulls (but also lions or griffins). These did structural work (bearing cedar or palm beams) and symbolic work (strength, vigilance, royal guardianship).

- Courtyards: six in all across the broader complex (with three principal courts), providing ventilation, illumination, and processional staging.

- Complex scale: across the Apadana and its adjunct suites the remains attest to over a hundred rooms and halls, integrated by broad corridors that managed the flow of delegations and guards.

In effect, it was a machine for audiences—the spatial grammar of empire translated into stone, brick, and light.

Colour and Code — The Glazed Brick Iconography

Inside and along approach walls, glazed brick panels displayed a disciplined visual language:

- The Immortals: rows of elite guards in patterned robes, step by step identical yet individually rendered—unity in diversity.

- Winged lions and griffins: liminal guardians of threshold and power.

- Lotus and blue water-lily: purity, rebirth, the ever-renewing order of the king’s justice.

- Royal palettes: deep blues, sun-yellows, whites, and blacks—sky, radiance, truth, and permanence.

The programme reads like imperial scripture: it teaches more than it decorates, training the viewer to see the Achaemenid cosmos as calm, balanced, and perpetual.

Empire in Stone — Artisans of Many Lands

Darius tells us plainly: craftsmen from across the empire built Susa, Elamite masons, Babylonian brick-makers, Lydian and Ionian stone-cutters, Egyptian goldsmiths. This is ideology by workforce. The palace itself becomes a multi-ethnic artefact, the material proof of a policy often summarised as governance through inclusion: peoples keep their customs and gods; they contribute their skills to something grander than the sum of its parts.

Palace of Light — Function, Ceremony, and Daily Rhythm

Susa functioned as the winter residence of the Great King; the Apadana was its public heart. Here satraps, envoys, and tribute bearers processed beneath the open porticoes to present gifts and petitions. Courtyards facilitated seasonal comfort, and acoustic volumes allowed proclamation before large assemblies.

Ceremonies did political work—legitimising succession, displaying clemency, fixing tribute, and consolidating alliances. The king’s visibility inside an “open” hall mattered: royal power was not hidden in inner sanctums but staged as law in the daylight.

Fire and Renewal — From Artaxerxes I to Artaxerxes II

Ancient sources and archaeological layers indicate major fire damage during Artaxerxes I (traditionally dated 5th century BCE), followed by repairs and reconstructions under Artaxerxes II. Replacement column drums, patchwork brickwork, and reused capitals bear witness to a palace that survived and adapted, a physical palimpsest of Achaemenid longevity.

Fall and Afterlife — From Alexander to the Louvre

Like much Achaemenid grandeur, Susa’s Apadana suffered in the wake of Alexander’s conquest. Later centuries quarried stone and repurposed brick. In the late 19th century, extensive excavations by Jane & Marcel Dieulafoy and Jacques de Morgan revealed column bases, glazed friezes, and those iconic bull capitals, many of which went to the Louvre Museum.

One oft-quoted, rueful anecdote from the period captures the mixed legacy of early archaeology—wonder and violence:

“Yesterday I beheld with sorrow a colossal stone bull… In a fit of despair, I struck it; the head split like ripe fruit.”

Today, pedestals and fragments remain at Susa—stern, eloquent—and the masterpieces abroad continue to educate a global public about Iran’s first empire.

Registration, Conservation, and Meaning Today

On 1 October 2001, the Apadana of Susa was inscribed as Iran National Heritage No. 3981. Conservation has focused on stabilising brick masses, mapping column bases, and protecting surviving glaze fragments from salt and seasonal humidity. Replica displays and site interpretation attempt to reunite the scattered palace in the visitor’s imagination.

Yet the palace’s deepest meaning is not merely archaeological. The Apadana is a theory of rule rendered architectural:

- Open to the heavens (porticoes and light),

- Held by strength (animal capitals),

- Governed by order (orthogonal plans, measured processions),

- Sustained by plurality (many peoples building one house).

Susa’s hall is not simply where a king sat; it is how a king spoke, even in silence.

Sources & Further Reading

- Darius I: Foundation inscriptions from Susa and Persepolis (Old Persian/Elamite/Babylonian versions). https://www.livius.org/sources/content/achaemenid-royal-inscriptions/dsf/

- Stronach, D. “The Royal Road System of the Achaemenids,” Iranica Antiqua 24.

- Curtis, J. Ancient Persia. British Museum Press.

- Potts, D. T. The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge University Press.

- Dieulafoy, J. & M. L’Acropole de Suse and excavation reports (late 19th c.).

- Louvre Museum Collections: Achaemenid glazed bricks and animal capitals from Susa.

Leave a comment