The Concept of “Pardis”

In the arid landscapes of ancient Persia, the concept of the garden—known as “Pardis” (from the Old Persian pairi-daeza, meaning “walled enclosure”)—emerged not just as a space of beauty and cultivation, but as a powerful symbol of paradise. These gardens were meticulously designed to represent an idealized version of the natural world, one that mirrored the divine order and reflected the Persian ethos of harmony between man and nature.

The significance of Persian gardens extends beyond their aesthetic appeal. They were deeply intertwined with the cultural, religious, and political life of the empire, serving as spaces for contemplation, relaxation, and royal ceremonies. The word “paradise” in English, and its equivalents in many other languages, can trace their roots back to this Persian concept, underscoring the profound impact these gardens have had on the world’s cultural lexicon.

Persian Garden Design: A Glimpse into Paradise

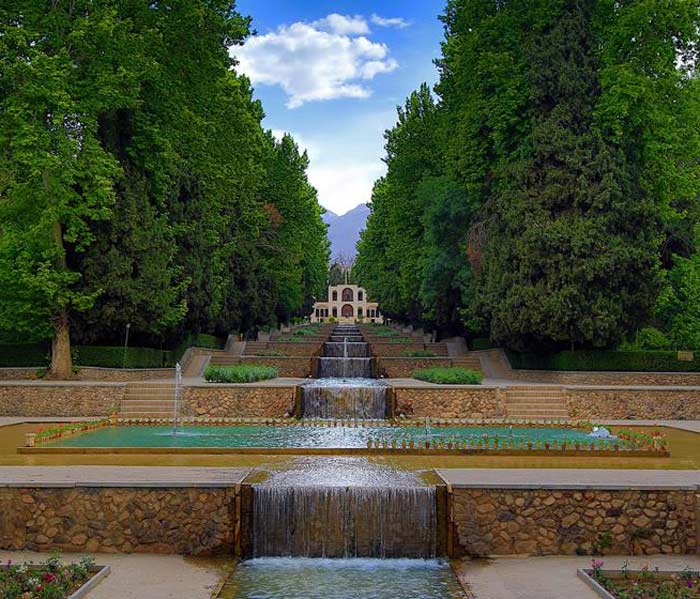

The design of Persian gardens was rooted in the idea of creating a microcosm of the world—an ordered, lush environment that contrasted sharply with the surrounding arid landscape. The Charbagh layout, which divides the garden into four quadrants, was a common feature, symbolizing the four Zoroastrian elements: earth, water, fire, and air. This layout was not just about symmetry; it was a spiritual reflection of the world’s order as understood in Persian cosmology.

Water was a crucial element in Persian gardens, not just for its life-giving properties, but for its symbolic meaning. The sight and sound of flowing water in canals and fountains represented purity, life, and the continuity of creation. In gardens like Bagh-e Fin in Kashan, water channels lined with cypress trees created an atmosphere of serenity and abundance, embodying the Zoroastrian reverence for water as a sacred element.

The choice of plants in these gardens was also symbolic. Cypress trees, with their evergreen foliage, represented immortality, while fruit trees symbolized fertility and life. Flowers such as roses and lilies were chosen for their beauty and fragrance, adding to the sensory experience of the garden. These gardens were designed to be not just seen, but experienced with all the senses—an embodiment of paradise on earth.

The Pasargadae Garden, created by Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BCE, is one of the earliest examples of a Persian garden. It was a place of both beauty and power, a space where Cyrus could demonstrate his dominion over nature and his connection to the divine. The garden’s design, with its geometric layout and carefully arranged water channels, set the standard for Persian garden design for centuries to come.

The Spread of “Pardis” Across Cultures

The influence of Persian gardens spread far beyond the borders of the Achaemenid Empire. As Persian culture interacted with other civilizations through trade, conquest, and diplomacy, the concept of the garden as a paradise began to take root in other parts of the world.

The Greek adaptation of the word pairi-daeza into paradeisos illustrates how this concept was absorbed and transformed by other cultures. When the Greeks encountered the lush, walled gardens of Persia during their campaigns, they saw in them an idealized version of the natural world, a place of peace and abundance. This idea of the garden as a sacred, enclosed space was carried into Hellenistic culture and later into Roman thought.

The spread of Islam in the 7th century further propagated the Persian garden’s influence. Islamic rulers in Spain, North Africa, and India adopted the Persian garden’s principles, integrating them with local traditions and the Islamic emphasis on water and shade as symbols of paradise. The gardens of the Alhambra in Spain, with their intricate water features and lush vegetation, owe much to the Persian garden tradition.

Perhaps the most famous example of Persian influence is the Taj Mahal in India. The gardens surrounding this iconic structure are a direct reflection of Persian garden design, with their Charbagh layout, water channels, and carefully planned symmetry. The Taj Mahal’s garden is not just a space for aesthetic enjoyment; it is a metaphor for paradise, a place where the earthly and the divine meet.

In Europe, the Renaissance saw a revival of interest in classical antiquity, including the Persian-influenced ideas of garden design. The formal gardens of Italy and France, with their emphasis on symmetry, order, and the interplay between architecture and nature, were in many ways a continuation of the Persian garden’s legacy.

Cultural and Religious Significance

In Persian culture, gardens were not just physical spaces; they were also metaphors for paradise, a theme that permeates Persian literature, art, and religion. The garden, or bustan, is a recurring motif in Persian poetry, symbolizing love, beauty, and spiritual enlightenment. Poets like Hafez and Saadi often used the imagery of gardens to explore themes of divine love and the ephemeral nature of life.

In Zoroastrianism, which was the dominant religion in Persia before the rise of Islam, gardens held a special significance. They were seen as reflections of the divine order, places where the physical and spiritual worlds intersected. The care of gardens was considered a form of worship, an act of maintaining the balance between the forces of good (Ahura Mazda) and evil (Angra Mainyu).

Gardens also played a central role in the political and ceremonial life of the Persian Empire. Royal gardens were spaces where the king could demonstrate his power and control over nature, hosting foreign dignitaries and conducting state affairs in a setting that symbolized the empire’s wealth and sophistication. The gardens of Persepolis, for instance, were not just places of leisure; they were integral to the empire’s image of prosperity and divine favor.

Legacy and Preservation

Today, many Persian gardens are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage sites, celebrated for their cultural and historical significance. These gardens have survived the ravages of time, war, and changing political regimes, standing as testaments to the enduring appeal of Persian design principles.

Bagh-e Fin in Kashan, with its ancient water channels and towering cypress trees, is a prime example of the resilience of Persian garden design. Despite numerous renovations and changes over the centuries, the garden still retains its original layout and atmosphere, offering a glimpse into the past.

Bagh-e Eram in Shiraz, another UNESCO site, is renowned for its collection of rare plant species and its beautiful pavilion, which blends Persian and Qajar architectural styles. The garden’s design, with its emphasis on harmony and balance, reflects the core principles of Persian garden philosophy.

In contemporary landscape architecture, the influence of Persian gardens can still be seen. The use of water features, geometric layouts, and the integration of natural and built environments are all hallmarks of Persian design that continue to inspire garden designers around the world. The concept of the garden as a sanctuary, a place of retreat and reflection, remains as relevant today as it was in ancient Persia.

The preservation of these gardens is not just about maintaining physical spaces; it is about preserving a way of seeing and interacting with the world. Persian gardens represent a unique intersection of culture, nature, and spirituality, offering lessons in sustainability, beauty, and the human connection to the divine.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Persian Gardens

The Persian garden is more than just a historical artifact; it is a living tradition that continues to inspire and captivate. From their origins in the arid landscapes of ancient Persia to their influence on global garden design, Persian gardens embody the timeless human desire to create spaces of beauty, peace, and harmony.

As we walk through these gardens today, whether in Iran, Spain, India, or beyond, we are reminded of the universal appeal of the paradise paradigm. In a world that often seems chaotic and disconnected from nature, Persian gardens offer a vision of balance, where the boundaries between the natural and the divine are blurred, and where beauty and order reign supreme.

Leave a comment