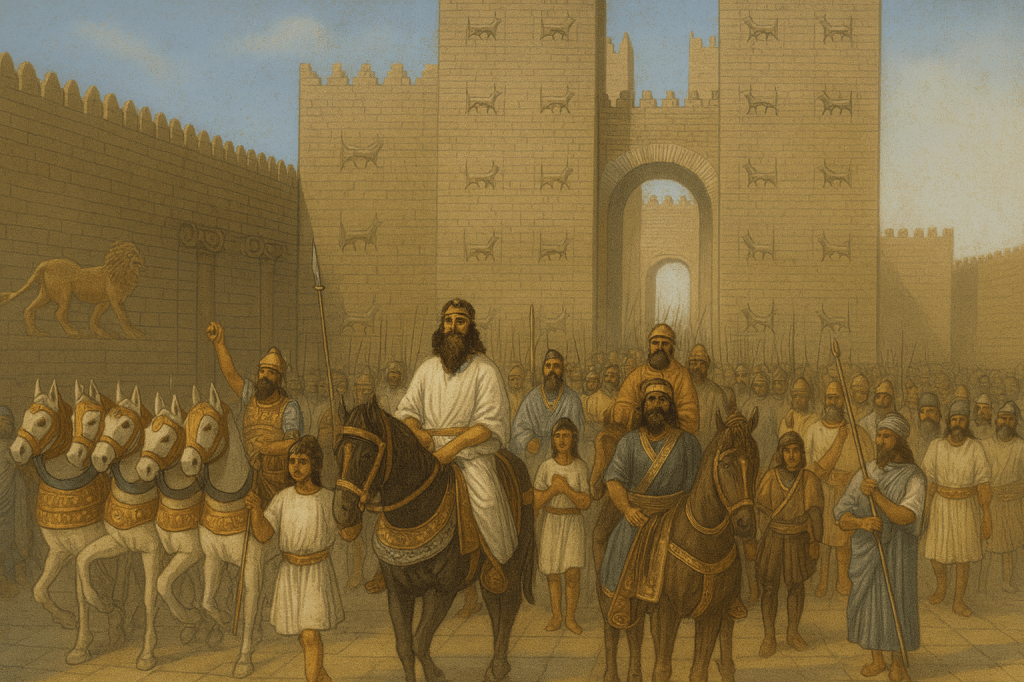

Above picture: Courtesy of Ancient History Magazine / Karwansaray Publishers [link to the image]

When Cyrus the Great marched into Babylon in 539 BCE, he did not destroy its temples, dismantle its institutions, or erase its memory. Instead, he proclaimed himself the liberator of its people, the restorer of its sanctuaries, and the rightful heir to its ancient kingship. Babylon — with its millennia-old legacy of law, ritual, administration, and architecture — was not conquered; it was absorbed. And in doing so, it became one of the pillars of Persian imperial ideology.

This article explores how the Persians inherited and reinterpreted Babylonian models of kingship, governance, religion, and culture — not merely as colonisers, but as successors to a civilisation that had long defined what it meant to rule.

Babylon: The City of Kings and Temples

Babylon’s roots stretch back to the third millennium BCE, but it was under rulers like Hammurabi, Nebuchadnezzar II, and Nabonidus that it rose to prominence as the beating heart of Mesopotamia. By the 6th century BCE, Babylon was a thriving metropolis — home to monumental architecture, a thriving scribal class, astronomical observatories, and a deeply entrenched tradition of temple-state governance.

To be king of Babylon was not merely to hold political power; it was to assume a cosmic role. The king stood as the intermediary between gods and people, restorer of maat (order), protector of temples, and guardian of the land’s fertility. His legitimacy came from divine approval, enacted through rituals in the great temple of Esagila, and affirmed during the Akītu (New Year) festival.

Babylon was more than a city. It was a model of sacred kingship, a blueprint for rule that combined justice, piety, and civic order.

The Persian Conquest: Strategy, Not Destruction

Cyrus’s capture of Babylon is notable not for its violence, but for its restraint. According to both the Nabonidus Chronicle and the Cyrus Cylinder, the city fell with little resistance, its inhabitants welcoming the Persians as liberators from an unpopular regime.

What followed was remarkable: Cyrus entered Babylon not as a foreign conqueror, but as a king in the Babylonian mould. He presented himself as chosen by Marduk, Babylon’s chief deity, and promised to restore neglected temples, return displaced peoples to their homelands, and rule with justice and peace.

This political performance was deeply Babylonian. Cyrus understood that to rule Mesopotamia effectively, he needed to align with its religious and ideological traditions. The Cyrus Cylinder, often hailed as an early declaration of human rights, is more accurately read as a Babylonian-style royal inscription — full of traditional formulas, appeals to the gods, and affirmations of the king’s duty to restore cosmic balance.

Credit: Image generated by AI (ChatGPT with DALL·E), based on historical references and public domain artwork.

Administrative Inheritance: Scribes, Temples, and Archives

The Persians inherited not just Babylonian symbolism, but its infrastructure of governance. Babylon was home to elite scribes trained in cuneiform, who managed contracts, tax records, astronomical charts, and legal codes. Rather than abolish this class, the Achaemenids retained and empowered them.

Achaemenid rulers allowed Babylonian language and script to remain in use for temple administration and legal affairs. They also maintained the temple estates, which functioned as economic engines, landholders, and centres of social stability. Temples like Esagila and Eanna (in Uruk) continued to operate under imperial supervision, but with a high degree of religious autonomy.

Babylonian scholars continued to observe the stars, compile omens, and preserve ancient texts — much of which would later influence Hellenistic science and astronomy. The Persian approach was not to overwrite Babylon, but to institutionalise it as a provincial yet essential partner.

The Babylonian Model of Kingship: Influence on Achaemenid Rule

Babylonian kingship was defined by a close relationship between the monarch and the divine order — not unlike later Zoroastrian ideals of asha. A Babylonian king was a builder of temples, restorer of justice, punisher of the wicked, and protector of land boundaries.

The Achaemenid kings adopted many of these roles. Darius I, for example, described himself not only as a king by lineage, but as one who governed according to truth and punished lies — a direct parallel to Babylonian royal ethics.

Both traditions emphasised the king as the steward of universal order. Both built massive infrastructure (canals, roads, walls). And both used inscriptions — whether on stelae, bricks, or clay cylinders — to record their deeds as sacred obligations.

Even the multi-language inscriptions of the Achaemenids (e.g., Behistun) reflect a Babylonian scribal habit of polyglot administration and archiving.

Cultural Synthesis: From Temples to Persepolis

The influence of Babylon extended even into Persian art and architecture. While the style of Persepolis is distinctly Iranian, it incorporates Mesopotamian structural principles — massive columns, multi-tiered reliefs, and axial symmetry drawn from Babylonian and Assyrian palatial design.

Court rituals, tribute processions, and calendrical observances also bear the imprint of Babylonian practice. The imperial year was punctuated by festivals, just as Babylon’s was anchored in religious ceremony. And the idea of the king receiving offerings from subject peoples — seen on the staircases of Persepolis — echoes the processions once staged in Babylon’s temples.

From Heirs to Successors: Persian Legitimacy in Babylon

The Persian kings did not simply use Babylon as a province — they claimed it as a co-capital, a sacred city in their imperial vision. Babylon remained a vital administrative centre through the Achaemenid period, and its elites continued to serve the empire even as power shifted to Susa, Ecbatana, and Persepolis.

By adopting the Babylonian model, the Persians positioned themselves as legitimate successors to Mesopotamian history. They framed their empire not as a rupture, but as a continuation of a sacred order — one that began with Sumer, passed through Akkad and Babylon, and now flowed into Iran.

Conclusion: Babylon’s Empire Within an Empire

The Persian Empire did not rise by flattening the cultures it encountered. Instead, it rose by absorbing, adapting, and preserving them. Babylon, with its sophisticated ideology of kingship and its millennia-old systems of administration, was not an obstacle to Persian rule — it was a foundation.

From Cyrus’s respectful entry to Darius’s scribal policies and Xerxes’s temple restorations (and suppressions), the Persian encounter with Babylon shaped the very nature of Achaemenid governance.

In adopting the Babylonian blueprint, Persia transformed itself — not into a copy of Mesopotamia, but into its most successful heir. An empire that ruled not just by sword or gold, but by myth, memory, and the mastery of inherited order.

Leave a comment