No.34

Though fair my face, though bright my hair may be,

My tulip cheeks and cypress stature you see;

Yet still I know not why, in earth’s joy-house,

The Eternal Painter chose to adorn me. *

Philosophical Reflection

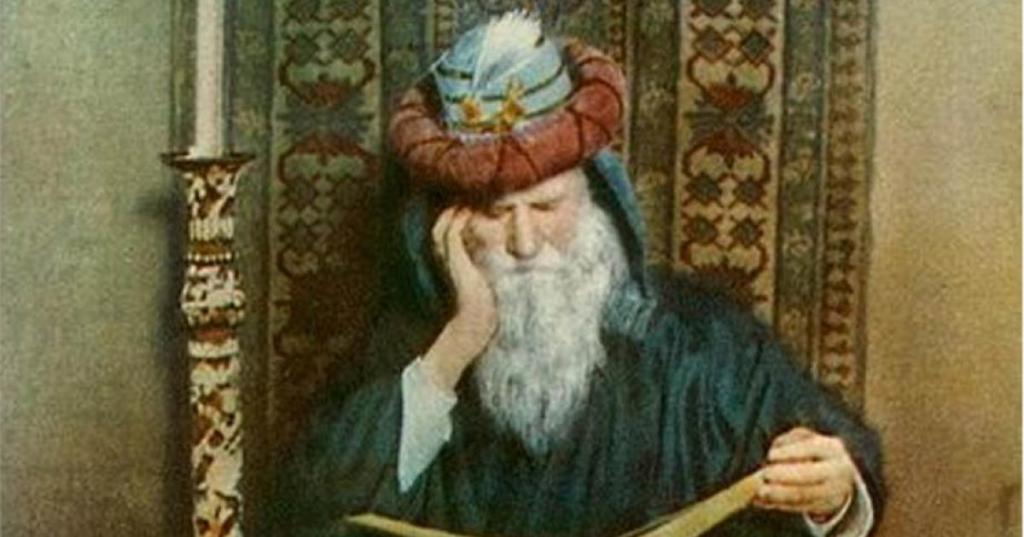

In this quatrain, Khayyam turns his gaze toward beauty itself — not as vanity, but as a philosophical problem. The opening lines catalogue physical grace with almost classical restraint: a fair face, bright hair, cheeks likened to tulips, a stature compared to the cypress. These images are conventional in Persian poetry, yet Khayyam employs them without self-celebration. Beauty is stated plainly, almost clinically, as an observed fact rather than a source of pride.

The real tension appears in the third line. Despite possessing these outward gifts, the speaker confesses ignorance about their purpose. The world is described as a “joy-house of earth,” a place of temporary delight, yet within this space the reason for such careful adornment remains unknown. Beauty, usually treated as a sign of divine favour or intentional harmony, becomes instead a riddle.

The final line sharpens the question by naming the creator as the “Eternal Painter.” The metaphor is deliberate: a painter chooses colours, forms, and proportions with intention. If so, why is the subject of this artistry left unaware of its purpose? Khayyam does not deny creation, design, or skill; he questions meaning. Why adorn what will fade? Why grant beauty to a form destined for dust? The unease lies not in transience alone, but in unexplained intention.

This quatrain belongs primarily to The Challenge of Creation, while also touching Meaning & Doubt. It resonates with Khayyam’s broader reflections on purpose and design found in On the World and the Duty, where the structure of existence is examined without recourse to comforting answers. It also aligns with Treatise on Being, which explores existence without assuming inherent justification, and A Response to Three Questions in Philosophy and Theology, where divine intention is subjected to rational scrutiny.

Khayyam’s insight here is subtle yet unsettling: beauty does not guarantee meaning. One may be exquisitely formed and yet remain ignorant of why one was formed at all. The quatrain leaves us with a quiet, enduring question — not whether creation is beautiful, but whether beauty itself explains creation.

Footnote

* Source: Trabkhaneh, Homaei, no. 34, translated by Kam Austine for the book Philosophy in Verse

هر چند که روی و موی زیباست مرا

چون لاله رُخ و چو سرو بالاست مرا

معلوم نشد که در طربخانهٔ خاک

نقاش ازل بهر چه آراست مرا

Related Khayyam’s Treatises:

On the World and the Duty

Treatise on Being

A Response to Three Questions in Philosophy and Theology

Internal Themes: #ChallengeWithTheCreator #Purpose #Beauty #Meaning

Published as part of the Philosophy in Verse Series — under “The Challenge of Creation.”

Leave a comment