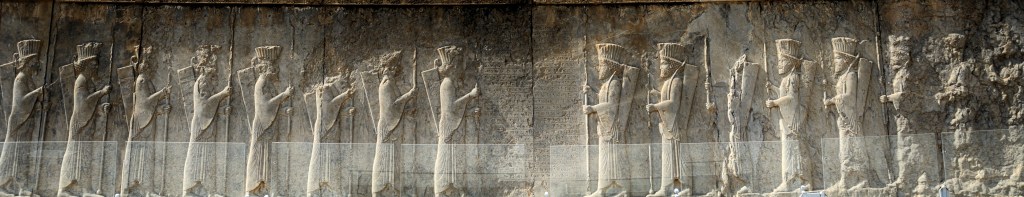

The reliefs of Persepolis do not tell stories. They do not narrate battles, commemorate victories, or record historical events. They repeat. Figures advance in measured rhythm. Processions unfold endlessly. The same gestures, the same offerings, the same calm faces recur across stairways and walls. This repetition has often puzzled modern viewers trained to expect narrative drama from monumental art. Yet in Persepolis, repetition is the message.

These reliefs are not historical illustrations; they are theological statements. They articulate a vision of power rooted not in domination, but in order — a political theology carved into stone.

Reliefs Without Time

Unlike Assyrian palace reliefs, which depict campaigns, sieges, and violence with striking realism, Persepolis is almost entirely free of historical time. No named enemies appear. No defeated kings kneel. No cities burn. Instead, the empire is shown as it ought to be, not as it was at any given moment.

Delegations from across the empire approach the king bearing gifts. Each group is distinct in dress and bearing, yet none is humiliated. They are neither slaves nor equals, but participants in a ritual order. This scene is repeated with minimal variation, reinforcing the sense that what is depicted is eternal rather than episodic [1].

In theological terms, Persepolis presents an empire outside history.

Repetition as Ideology

The repetitive nature of the reliefs is not artistic conservatism; it is ideological discipline. Repetition denies contingency. It suggests that the structure of empire is fixed, stable, and self-renewing. Nothing disrupts the rhythm. Nothing surprises.

By repeating the same scenes across different architectural contexts, Persepolis trains the viewer to internalise order as natural. Diversity exists, but it is harmonised. Motion exists, but it is controlled. Power exists, but it is distant.

This is not propaganda in the modern sense. It is closer to liturgy.

Symmetry and the Moral Geometry of Power

Symmetry dominates Persepolitan reliefs. Figures are balanced, mirrored, and aligned along horizontal axes. No figure intrudes into the space of another. The visual grammar communicates restraint, proportion, and hierarchy without aggression.

In this geometry, the king occupies the centre not by force but by inevitability. He is elevated, often seated, sometimes accompanied by a crown prince. He does not act; he receives. Authority flows toward him rather than emanating violently outward [2].

This reflects a conception of kingship deeply aligned with Zoroastrian ideas of aša — cosmic order maintained through balance rather than annihilation. The reliefs do not dramatise struggle; they assume it has already been resolved at a metaphysical level.

The Absent Enemy

Perhaps the most striking feature of Persepolis reliefs is the absence of enemies. This absence is itself theological. In a worldview where the king rules by divine sanction, opposition is not worthy of depiction. Disorder exists, but it does not belong in the sacred space of ritual kingship.

Where rebellion occurs — as in Darius’s inscriptions — it is framed as falsehood, deviation from truth, not as a legitimate rival. Persepolis, as a ritual site, excludes falsehood altogether. What remains is a purified vision of empire [3].

The King as Axis, Not Actor

The Persian king at Persepolis does not resemble the heroic rulers of Mesopotamian or Greek art. He does not strike enemies or hunt beasts. He presides. His stillness is essential. He is the axis around which the empire turns.

This stillness transforms kingship from action into presence. The king embodies order rather than enforcing it. In theological terms, he functions less as a warrior and more as a guarantor of cosmic balance.

This helps explain why the king’s image remains remarkably consistent across reigns. Individual personality is irrelevant. Kingship is an office, not a character.

Political Theology Without a Temple

Persepolis contains no temples to gods in the conventional sense. Yet the entire complex functions as a sacred space. Architecture, reliefs, movement, and ritual converge to create a theology of power without priesthood.

The Apadana, in particular, operates as a ceremonial sanctuary where the empire is symbolically gathered and reordered. Each delegation participates in reaffirming the cosmic legitimacy of Persian rule. The act of giving becomes a ritual of belonging, not submission.

This is theology enacted through politics.

Why the Reliefs Never Change

Across decades of construction and multiple reigns, the reliefs maintain extraordinary consistency. This continuity is not artistic stagnation but doctrinal fidelity. To alter the imagery would be to suggest that the nature of power itself had changed.

Instead, Persepolis insists on permanence. Even when kings change, the order remains. Even when empires expand or contract, the ritual vision endures.

This rigidity explains both the strength and fragility of Persepolis. It could not adapt — because adaptation would undermine its claim to timelessness.

Theological Vulnerability and Alexander

When Alexander burned Persepolis, he attacked not a city but a theology. The destruction was symbolic violence aimed at the very idea of Persian order. By destroying Persepolis, Alexander sought to shatter the illusion of timeless legitimacy [4].

Yet the theology did not disappear. Its influence persisted in later Iranian political thought, where kingship continued to be framed as moral stewardship rather than brute force.

Conclusion: Stone as Doctrine

Persepolis reliefs do not persuade; they assume. They do not argue; they reveal. Through repetition, symmetry, and ritual calm, they articulate a political theology in which empire is not conquest but order made visible.

To walk the stairways of Persepolis was to ascend into a worldview — one where power was measured by balance, legitimacy by continuity, and rule by harmony.

It is this vision, more than any battle or decree, that defined the Achaemenid Empire.

Footnotes

- Margaret Cool Root, The King and Kingship in Achaemenid Art, Brill, 1979.

- Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Amélie Kuhrt, The Persian Empire, Routledge, 2007.

- Robin Lane Fox, Alexander the Great, Penguin, 2004.

Leave a comment